In this paper, we dive deep into adapter-based fine-tuning methods, especially in the context of multilingual LLMs. As you may know, I am currently working with a multilingual automatic speech recognition model, and hopefully this paper will shed a light on how to fine-tune my model better.

So what is the problem with multilingual LLMs? If we consider vanilla fine-tuning, catastrophic forgetting is the main issue (in addition to expensive training time and compute). When we fine-tune on a new language, the performance for the older ones will degrade. On the other hand, if we do a non-intrusive parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT), we would need to train one for every new language, which is infeasible for low-resource languages.

So rather than training a separate adapter for each language, can we instead create a generator model that, given a typological representation of any language, output the adapter parameter for that language? This would then:

- Enable zero-shot adapter generation for any language, even for those never seen during generator training, as long as the typological representation is available.

- Contain shared capacity across languages, which could possibly drastically reduce parameters and training time per language.

The authors proposed MAD-G as the generator model for multilingual LLMs.

This blog will be broken down into the following parts:

Adapter-based fine-tuning

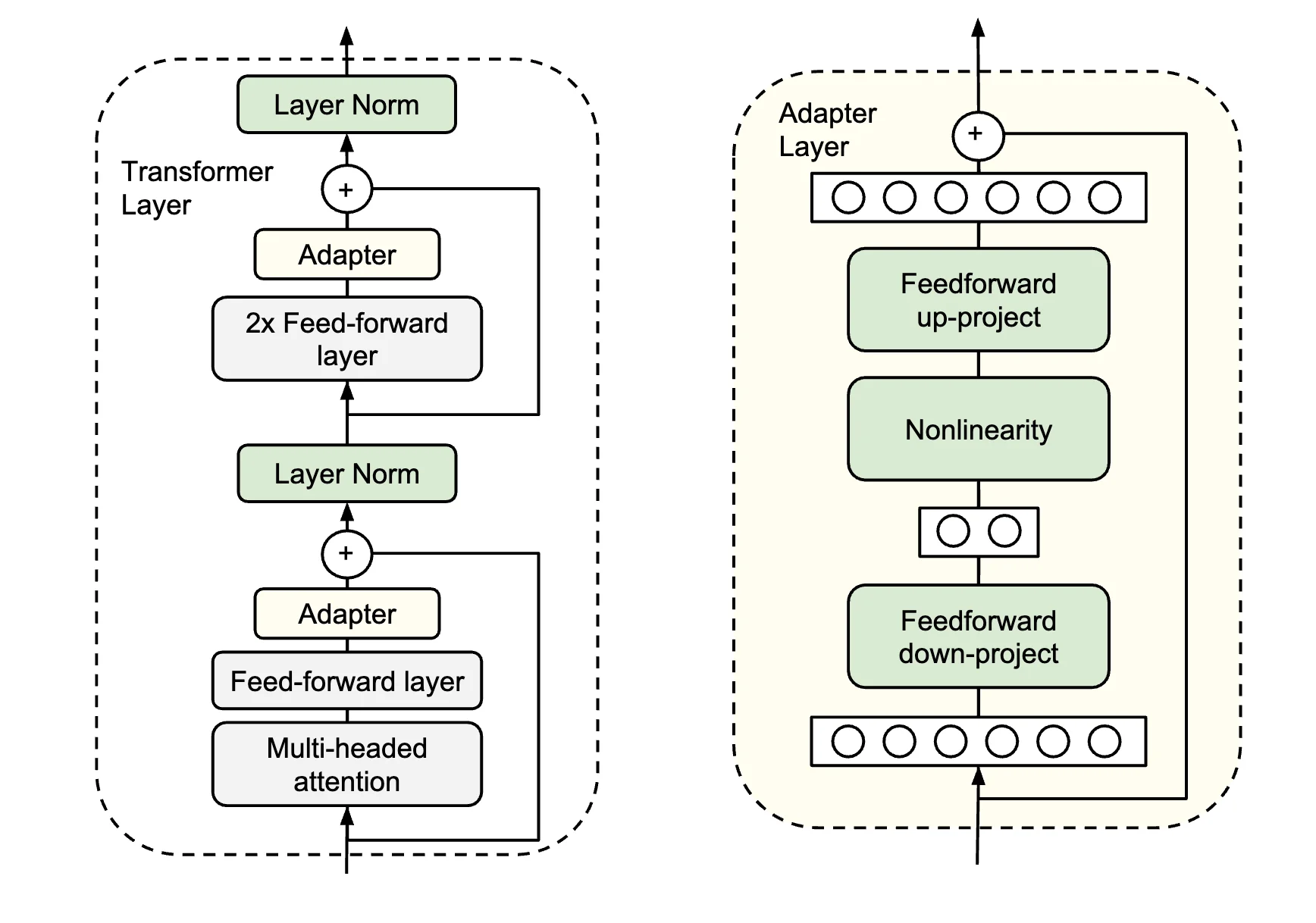

An adapter is basically a tiny “bottleneck” module inserted into each transformer layer. It consists of:

- Down-projection, where the hidden state layer is compressed from dimension to a small dimension .

- Nonlinear activation function, like ReLU.

- Up-projection, where the compressed hidden layer is expanded back from to .

- Residual addition, where the adapter’s is added back to the original hidden state.

What makes adapter-based fine-tuning so attractive?

- There is no change in the base model. The original model weights are frozen. Only the adapters parameters, i.e. those used in down-projection and up-projection, roughly per layer are trainable.

- Lightweight, as mentioned only a small fraction of the entire model parameter is trainable.

- Modularity, since we can train one adapter for each task (in this case, language), without touching the main model. At inference, we can simply “plug and play” the adapter depending on the language.

This paper is heavily inspired by the MAD-X paper, which uses adapters for multilingual tasks:

- Train one adapter per language via monolingual MLM.

- For a downstream tasks, like POS tagging, freeze the language adapter and add a tiny task adapter on top, and fine-tune only that.

- At test time, swap in the target-language adapter to solve the same task in different languages.

However, there is still a need to train (and store) one adapter per language. Hundreds of languages would mean a parameter blow-up. Also, low-resource language with little monolingual data can’t produce a good adapter.

From typology to adapter

To combat these problems, MAD-G uses typology representation to generate the adapter. Specifically, it leverages on the URIEL database.

URIEL Database

It is a large typology database that represents each language as a vector of linguistic features. For each language, the vectors represent:

- Syntax, such as word-order (SVO vs. SOV), case-marking, and morphological alignment.

- Phonological features, like presence of tone, vowel or consonant classes.

- Geographic influence, such as the distance between languages.

- And others.

In practice, MAD-G uses 289-dimensional URIEL vector, i.e. , for each new language . Each position corresponds to one typological attribute.

Contextual Parameter Generation

Instead of learning one adapter per language, we learn a single function (called the generator) that maps any URIEL vector into that language’s adapter weights correctly.

The full steps are as follow:

- Compress the URIEL typology representation.

- Let us learn a weight matrix

where is small (in the paper, ).

- Compute

where is a a small embedding capturing the distilled rich typological signature of language .

- Let us learn a weight matrix

- Generate full adapter weights.

- Suppose that our transformer model has layers, each with hidden size and adapter bottleneck .

- Each layer’s adapter needs two matrices, one for down-projection and another for up-projection:

- Stack all of these adapter parameters for in one big vector of size .

- We now learn another generation matrix

When we multiply with , we get length- vector:

- Finally, we reshape back into , and we get our adapter parameters.

Why Use and ?

- If we tried direct mapping from to , we would need a matrix of size , which is very big.

- Instead, we factorize by mapping ( and then which is orders of magnitude smaler since and .

Layer-Conditioned Variant (MAD-G-LS)

MAD-G’s original generator treats all layers identically; it generates all adapter parameters strictly from . However, different transformer layers capture different types of linguistic information. To allow more flexibility, MAD-G-LS introduces a layer-embedding, whereby:

- Learn a small embedding for each layer index .

- Concatenate (overall language embedding) and into a -dimensional vector.

- Use a smaller generator,

to produce layer-’s adapter parameters:

- Proceed as per normal for each layer.

In this way, each layer’s adapter benefits from both language signal (from ) and layer-specific bias (from ).

Training MAD-G

Training is just a matter of learning and . MAD-G does this via multilingual masked-language modeling (MLM).

- Freeze the base model throughout the training.

- Select a set of training languages that maximises typological diversity.

- On each training step, sample one language with probability porportional to . This is done to prevent over-sampling of high-resource languages.

- Sample a minibatch of masked-language modeling examples in that language.

- Forward pass

- Retrieve URIEL typology vector .

- Compute .

- Compute .

- Reshape into each layer down and up-projection.

- Modify the frozen transformer by adding the adapter.

- Run the standard MLM modeling objective, updating only and .

Downstream Use-Cases

After pre-training MAD-G (i.e. when and converged), the generator can now produce adapters for any language. Here are some of the use-cases

Zero-Shot Cross-Lingual Transfer

Similar to the MAD-X paper, as mentioned above, we would need to train a task adapter on top of the language adapter. Then, we can use the MAD-G adapter to create the different language adapter without being trained on the task directly.

Few-Shot Adapter Fine-Tuning (MAD-G-ft)

If you have some (not all) unlabelled text in low-resource language , MAD-G supports a hybrid method:

- Generate from URIEL.

- Fine-tune on MLM using those unlabelled tokens. Keep the base model frozen. This adapts the generator’s output towards the actual text distribution of language .

- Freeze the newly fine-tuned adapter .

- Plug the same task adapter (trained on source, different language) and run inference.

Multi-Source Training

Rather than fine-tuning the adapter in just English, we can use multiple source languages.

- For each source language , generate its adapter .

- On each task-adapter training step, randomly pick one source , activate and update only the task adapter on that language’s labelled data.

- At inference, you still generate for target language and then apply the same task adapter.

Key Experimental Results

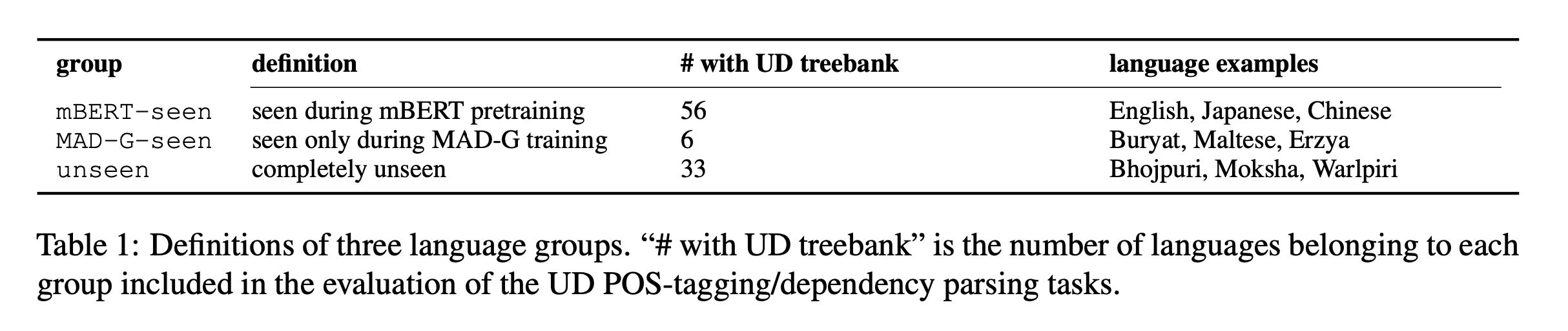

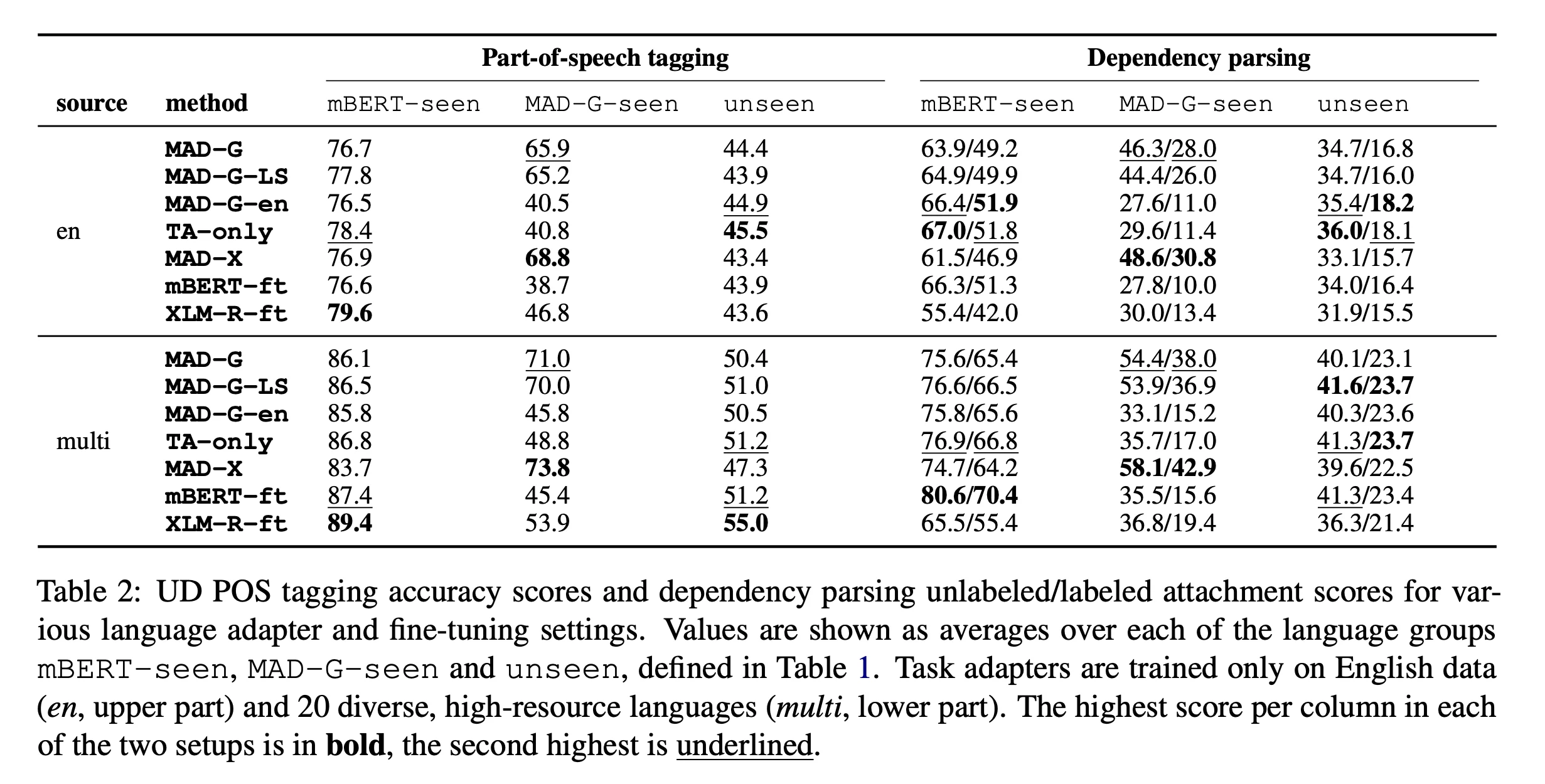

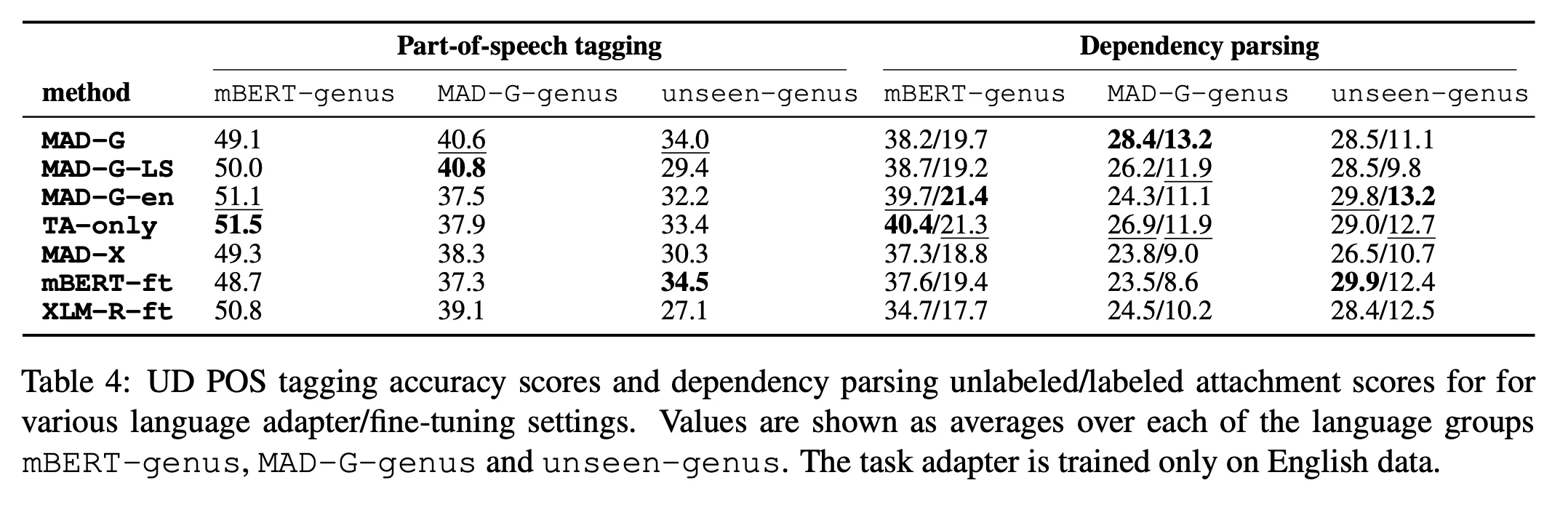

Single-Source Training

- Obviously, the use of MAD-G and MAD-G-LS are beneficial on all tasks for MAD-G-seen languages in both single and multi-source training scenarios.

- Interesting to note that the super parameter-efficient MAD-G-LS is only slightly weaker or sometimes outperform the original MAD-G in some languages.

- Also important to note that MAD-G is trained with multilinguality in mind, so the results for single-source transfer may not be impressive, especially compared to MAD-X that prioritize performance at the cost of time.

- Note that performance of MAD-G-en is worse than MAD-G in MAD-G-seen languages.

- This means that MAD-G actually generate meaningful adapters, at least for languages that it is trained on.

- MAD-G does not show improvements in mBERT-seen languages.

- This can be attributed to the robust pre-training of mBERT in the first place, resulting in good results.

- MAD-G also does not show improvements in unseen languages.

- May be because of languages in this set differ substantially from the training languages.

- Note that while MAD-G aims to generalize, it can only do so for languages whose ‘typology relative’ is available during training.

- In order to investigate this more, we should separate the unseen languages into three different types:

- mBERT-genus (21 languages whose genus matches to ≥1 language seen during mBERT training)

- MAD-G-genus (4 languages whose genus matches to 1 language seen during MAD-G training)

- unseen-genus (8 languages completely unrelated to training languages)

- As expected, there is improvements for MAD-G-genus unseen languages, but no improvements for unseen-genus. This confirm our intuition that there must be at least one typological relative available during training for cross-lingual generalization.

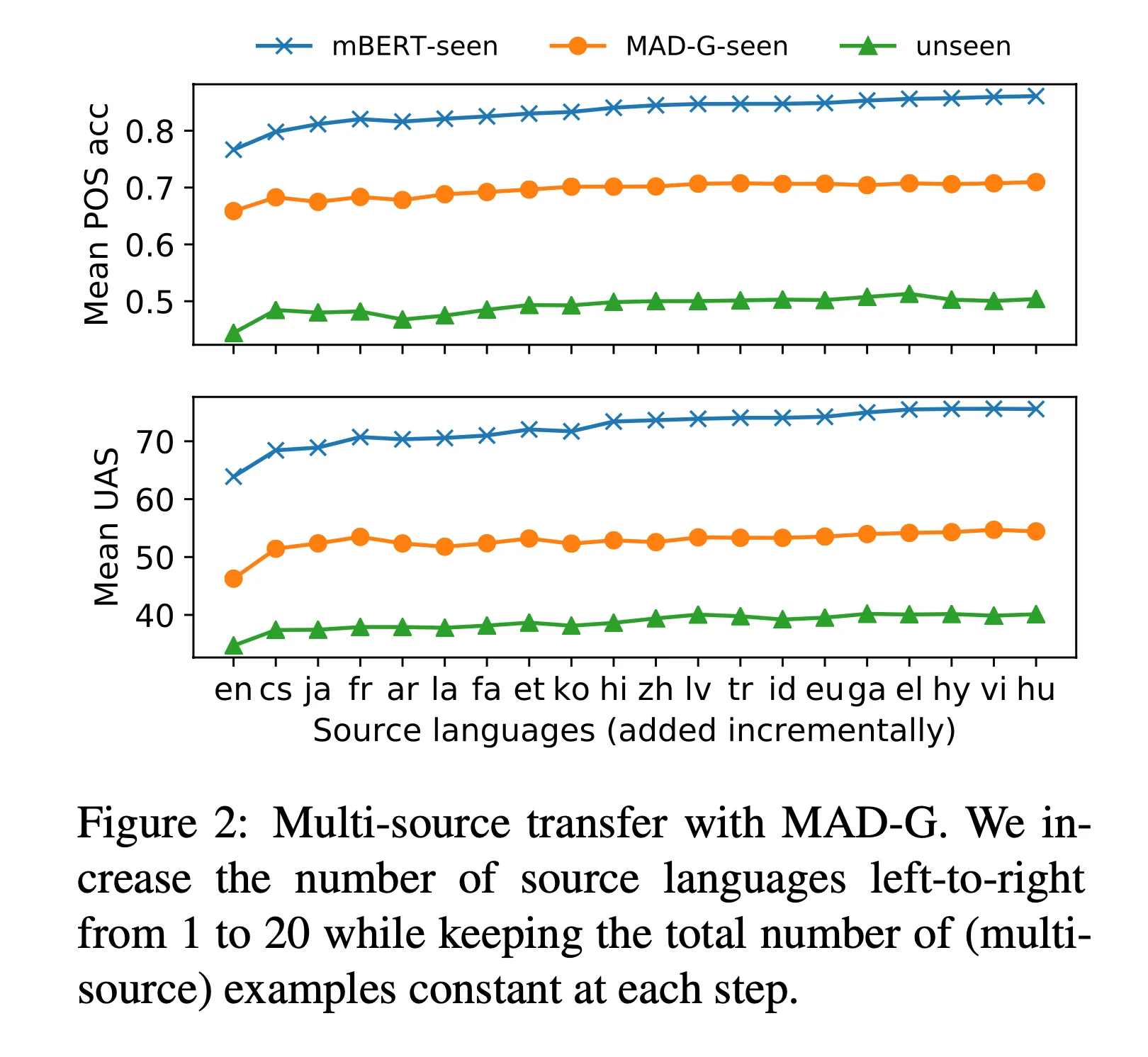

Multi-Source Training

- When we train on 20 languages, we observe large gains across all settings and language groups for both tasks.

- This shows that training with multiple languages is important in generalizing the task adapter.

- Figure 2 on the left shows the effect of multi-source training, where we gradually add languages into the multi-source pool.

- Transition between 1 to 2 languages yield highest improvement.

- However, performance still increased with addition of more languages.

- Basically, language diversity has positive effects on training.

My Thoughts

This is very very interesting, and very very relevant to what I am doing for my internship. I wonder how applicable this adapter-based fine-tuning methods to audio transformers.

I see that actually the improvements made by MAD-G is not the best, but I assume that it is because MAD-G is made to be a lightweight and flexible version of MAD-X. Another thing I’d like to point out is that this is a 2022 paper. Unfortunately, I do not follow adapter-based fine-tuning methods currently, so I am unsure if there is already a better way to switch from one language to another without the need to fine-tune rigorously.

Regardless, this is a very interesting paper, and I may attempt to reimplement it in audio transformer architecture.